My First Trip to Ancestral Homelands

My original goal in researching my family's history was to find out where each of my seven immigrant great grandparents and one great great grandparent were from. "From," of course is a fiction, because before my ancestors were from the places I set out to visit, their ancestors -- and sometimes even they themselves -- were from somewhere else. And in the big picture, all of humanity comes from Africa. Using a variety of sources -- ancestry.com, jewishgen.org, familysearch.com, Italian Genealogical Group, birth and death certificates, newspaper articles (on Fulton History, Brooklyn Newsstand, and ProQuest Historical Newspapers, for which many public libraries have subscriptions), Brooklyn family stories, and research done by the Jewish Heritage Research Group -- I identified 11 shtetls and four cities from which my ancestors came. In June and July 2016 I travelled with my younger son Oscar, and my partner Susan, to Poland, Belarus and Lithuania, which were in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Russia when my ancestors lived there.

My great-grandparents left their homelands between about 1867 and 1888 and assimilated quickly as Americans. My four grandparents learned English as their first language and Yiddish, my great grandparents mame loshen or mother tongue, was virtually lost within a generation. My great grandparents did not keep in touch with brothers, sisters or cousins left behind. My paternal grandparents even took their honeymoon to Europe in 1924 but did not go to either Belarus or Lithuania where their parents had been born.

I did not expect to find relatives on my trip. Growing up in the 1960s, I learned that Eastern European Jews were annihilated in the Holocaust but that those Jews were not my family. Because I was a fourth and fifth generation American I didn't feel a visceral connection to the Holocaust as the cousin or niece of those my great grandparents had left behind. While doing my research, though, I was surprised to learn that indeed, a fourth cousin and his family were shot in 1941 by Nazis and local Lithuanians, along with most of the other Jewish women, children and elders in his town.

Though no one in my immediate family personally knew anyone killed in the Holocaust I was still deeply affected by the genocide, having many nightmares of being pursued by Nazis and calculating, even to this day, which shoes and coat I would wear if I was rounded up. It never failed to surprise me when friends and acquaintances would ask me whether I would be visiting relatives on my trip. Surely they must know that virtually all Jews in that area were killed and that very few of those who survived, either in the camps or in hiding, had moved back.

My goal was simply to physically experience the places in which my foremothers and fathers had been – to walk on roads on which they had tread, to view the same forests, fields and rivers they must have seen, to look up at the same sky – and to look for cemeteries in which they placed their dead or any remnants of 19th century buildings. More than a century of climate change no doubt has altered the natural environment but I quickly learned that the Nazis and the Soviet Union most certainly had destroyed almost all of the Jewish community’s built environment.

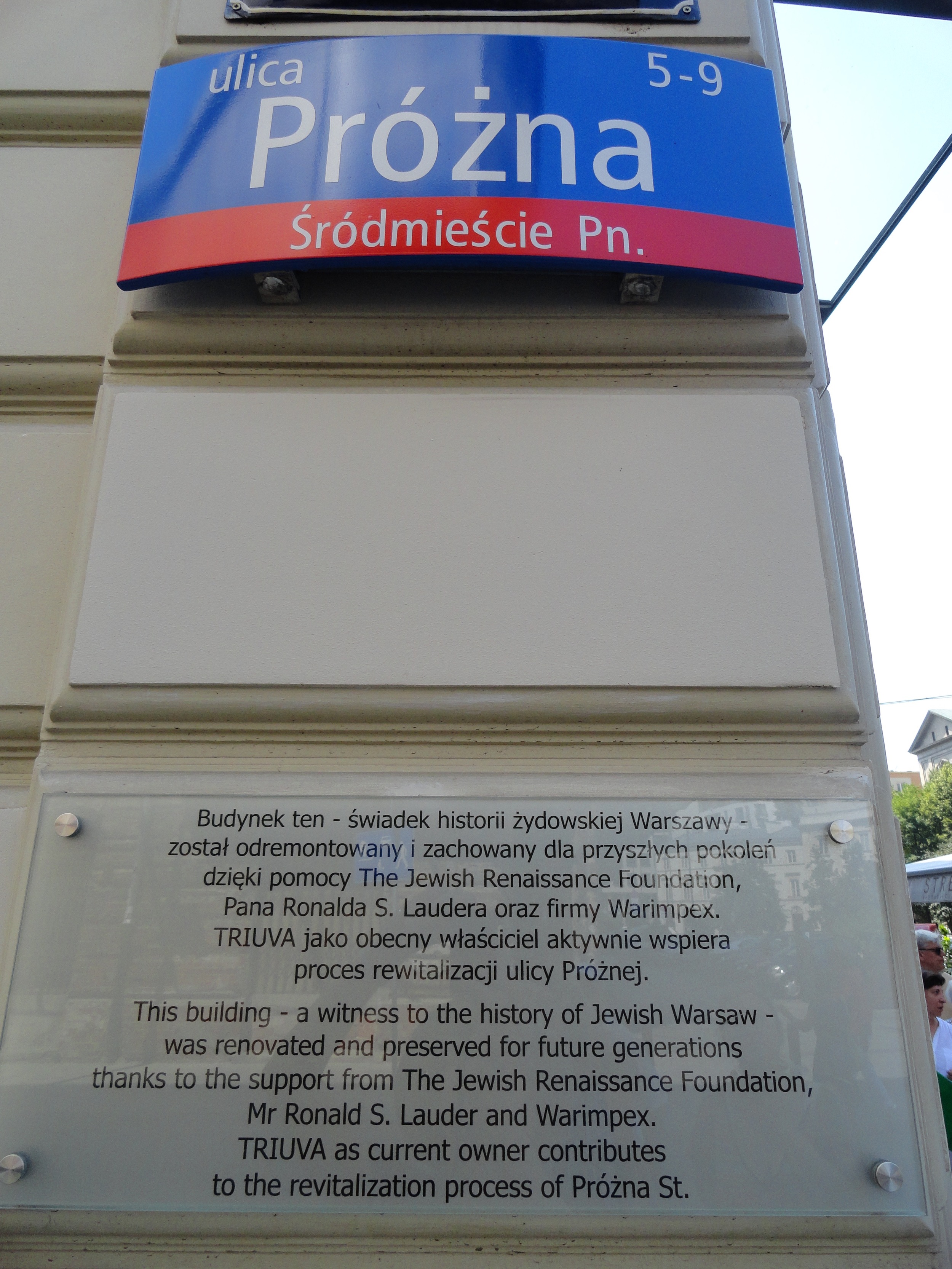

Since the Soviet Union’s break-up in the early 1990s, governments, NGOs and individuals, Jews and non-Jews, have attempted to mark the existence of Jewish communities in the cities, towns and villages of Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. In many cases, all that is left to see are these recent memorials.